N.B. Updated – 3 November 2021

In researching the lives of the Camp 020 interrogators, I had purposely left Second Lieutenant Winn to the last. I had very little information to go on and, since Winn was a rather common name and I had no first initials for the man, the odds of tracking him down seemed slim.

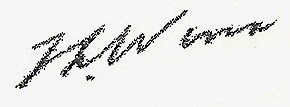

But persistence pays off. Whilst flipping through the KV 2 files on Josef Jakobs, in search of signatures for the other interrogators, I came across the signature of T.L. Winn, who had signed a report on behalf of Stephens. I had the key that I needed and, with that in hand, unlocked the British Army List and the London Gazette to uncover the story of Second Lieutenant Thomas Leith Winn.

Early Life

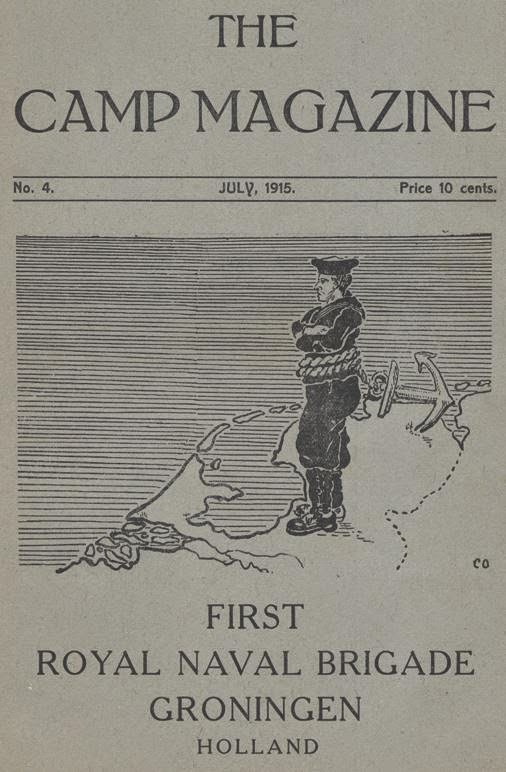

Leith (as he was known in later years) was born to Thomas Cromwell Winn and Marie Elmore Hilton on 29 November, 1894, in Hackney, London. Married in 1890, Thomas and Marie welcomed their first child with open arms and had him baptized at St. John of Jersualem Parish on 28 June, 1895. As a surgeon, Thomas was quite well-off and the family employed a cook and a nurse-maid. The nurse-maid came in handy, for by 1901, Leith had three younger siblings to shoo around the house, one sister and two brothers. At the age of 16, Leith was employed as a Merchant’s Clerk for an Iron Foundry, but his ultimate destiny lay elsewhere.

In 1913, while enrolled as a pharmaceutical student, Leith joined the Naval Reserve. Of average height, with fair hair and blue eyes, one of Leith’s main qualification as Able Seaman was his ability to swim.

World War I

On 2 August, 1914, Leith was called up to the Naval Training Depot at Chatham, also known as H.M.S. Pembroke. After a short training period, on 17 September, Leith joined the Hawke Battalion of the 1st Brigade. Despite having signed up with the Navy, Leith would see military action on land when he and his unit were sent to Belgium to help defend the city of Antwerp against the Germans.

As the Germans advanced, they threatened to encircle the city and the Belgian and British troops retreated via the River Schelde. Unfortunately, some of the British battalions from the 1st Brigade, including Leith’s Hawke Battalion, did not received the order to retreat until too late. By the time they had crossed the river and reached the railway, they had missed the last train out. With the Germans hot on their heels, Commodore Henderson, commander of the 1st Brigade, marched his troops into neutral Holland where the sailors were interned for the duration of the war.

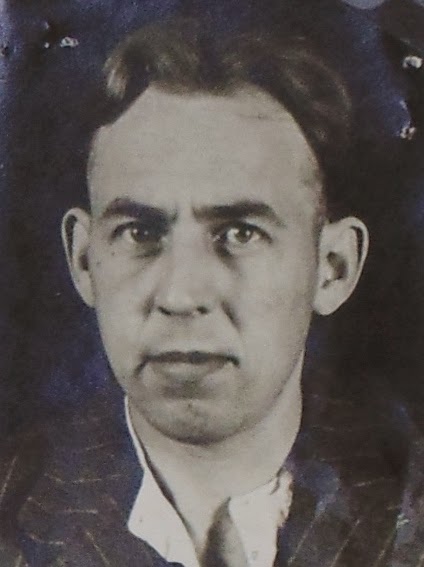

Leith and his fellow seamen were housed in wooden barracks in Groningen. A variety of activities were organized to prevent the troops from getting demoralized. The sailors had a daily routine of exercise, march and practice along with a variety of music, drama and sports clubs. A camp newsletter was even published on a regular basis. By 1917, the Dutch commander of the camp had arranged for the British seamen to be sent home on general leave, usually of a month or two month’s duration.

In June 1917, Leith received leave from Holland for several weeks (expiring 26 July 1917). A second leave was granted from 17 April, 1918 to 26 May, 1918. Finally, on 19 November, 1918, Leith and his mates from the Hawke Battalion were repatriated home.

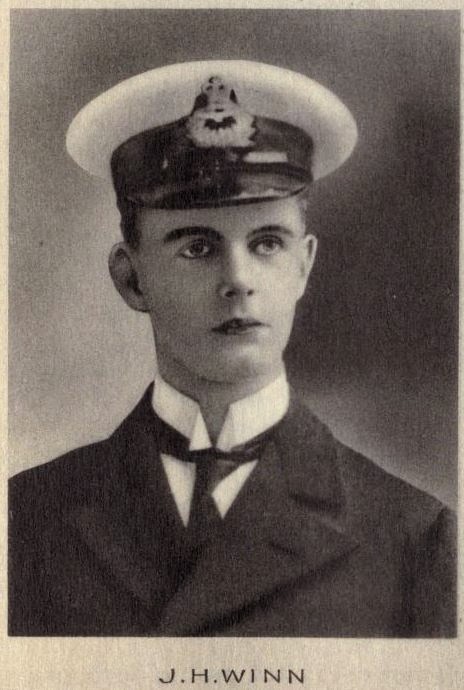

While Leith’s military adventures had ended with “safe” internment in Holland for the duration of the war, his younger brother, John Hilton, was not so fortunate. John was born in January 1899 and after studying in London, entered the service of Lloyds in 1915. In April, 1916, John joined the staff of the Bank of Montreal in London but only remained there for a year. In March, 1917, two months after turning 18, John enlisted for overseas service and immediately received a commission into the Royal Naval Air Service.

In the summer of 1917, having received his Pilot’s certificate, John was sent to France where he was attached to the 1st Naval Air Squadron at Bailleul as a newly qualified Flight Sub-Lieutenant. John ended up flying the Sopwith Triplane and had a few crack-ups. On 20 August, 1917, John emerged unscathed after his plane crashed during take-off because the engine choked. A few weeks later, John landed a tad too fast and collided with another plane.

On 20 September, 1917, John and his plane did not return from a flight over enemy lines and he was listed as “missing”. He and a few of his mates had gotten into a scrap with some Germans over Becelaere, Belgium. While John was credited with one “out of control” victim, he appears to have crashed near “Kruisher” (possibly Kruiseke, southeast of Gheluveldt). Word of John’s death would have been slow to reach Leith but when it did, he must have chafed with frustration. He and 1400 other able-bodied men were twiddling their thumbs in Holland while the war raged on without them.

Having returned to England in November 1918, Leith was attached to the Second Reserve Battalion in February 1919. He picked up his interrupted studies, this time as a student of dentistry. In early March, Leith was attached to the Command Dental Laboratory at Aldershot. A few months later, in July, Leith was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis (fibroid phthisis). Doctors determined that the condition was attributable to his military service and recommended that Leith be discharged. A month later, on 21 August, 1919, Leith was discharged with a 40% disability.

Fibroid phthisis was a chronic lung disease in which fibroid tissue would slowly grow in the affected lung. Over a long period of time, the lung would be reduced in size, become hardened and dense. The latter stages of the disease were more serious. But, at his young age, Leith was not going to let a lung disease distract him from his course.

By 1925, Leith had completed his studies and received his Licentiate in Dental Surgery. Leith’s father passed away in 1924 at the age of 64, and Leith ended up living with his mother at 57 Buxton Road, Chingford, a suburb of London. Over the next 25 years or so, Leith continued to practice dentistry in London.

In 1930, Leith attended the wedding of his younger brother, Kenneth, to Florence Elsie Jones. There is, however, no evidence that Leith himself ever married.

Dental Training (added 2021)

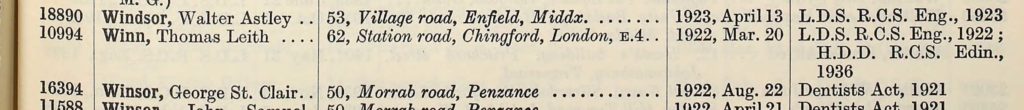

I tracked down the UK Dental Register and found our friend Leith listed throughout the 1930s. The register from 1940 is quite illuminating.

In 1940, Thomas Leith Winn was residing at 62, Station Road in Chingford, London. This is the same address we have come across and was also the same residence as his mother. Leith was registered as a dentist on 20 March 1920. That same year, he was also received an L.D.S. (License in Dental Surgery) and was admitted to the R.C.S. (Royal College of Surgeons–England). In 1936, he also received an H.D.D. (Higher Dental Diploma) and was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons–Edinburgh.

The Dental Surgeon’s Directory from 1925 has a brief entry for Leith:

WINN, Thos. Leith, 57, Buxton Rd., Chingford, London, E.4–L.D.S. R.C.S. Eng. 1922; (Utrecht & Guy’s); Dent. Off. Dame Colet Treatm. Centre, Stepney; Mem. B.D.A.

From this, we can deduce that Leith studied dentistry at Utrecht (Holland) and Guy’s Hospital in London. He would have been a newly qualified dental surgeon in 1925 and obviously spent his first few years practicing at the Dame Colet Treatment Centre in Stepney, London.

World War 2

In 1941, Leith was drawn into the war, receiving a Regular Army Emergency Commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps. Leith was assigned as an Intelligence Officer to Camp 020 and assisted Captain George F. Sampson at several interrogations of Josef Jakobs in April 1941. Major Stephens, Commandant of the Camp was a firm believer that spies would open up to interrogators who shared common interests – “A spy will talk ships to a man who knows little ships; he will talk desert war with a man who understands the meaning of thirst; he will talk Latin logic with a man who had the patience of Job.” Thus, Leith, the dentist, was assigned to assist in the interrogation of Josef Jakobs, the dentist.

Leith’s practical dental skills were also put to good use at Camp 020. In 1943, the Norwegian spy Nikolai Hansen arrived at Camp 020 and, after relentless interrogation by Stephens, finally admitted that the Germans had tucked some secret writing material into one of his teeth. Stephens later noted, “Now among the intelligence officers at Ham was one who in peacetime practiced dentistry. Hansen’s permission for the surgical operation was obtained, and the officer pulled Hansen’s tooth in the interrogation room, thus retrieving the secret material.” This dental Intelligence Officer was most likely our friend Leith.

Post War

References to Leith’s activities after the war are scarce. We know that he continued to practice dentistry in London until the early 1950s, acquiring a Higher Dental Diploma in the process.

By 1952, Leith and his mother had moved to 71 Castle-drive in Pevensey Bay, Sussex, perhaps to take advantage of the restorative properties of the sea air for Leith’s diseased lungs.

Pevensey Bay’s primary claim to fame was as the landing site of William the Conqueror in 1066. The Germans had eyed the same area as a potential landing site for Operation Sealion during the summer of 1940.

Perhaps Leith walked the shoreline of the bay and thought back to those wartime years when Britain’s fate hung in the balance. Leith and his fellow Intelligence Officers had played a significant role in confusing the Germans. It is doubtful, however, that Leith ever spoke of his time at Camp 020 as he died before the true story started to emerge from the cracks of time and wartime secrecy.

A year after moving to this historic locale, Leith’s mother, widow Marie Elmore Winn passed away at the age of 94, survived by her children, Leith, Gladys May and Kenneth. A newspaper article in the Eastbourne Gazette (Wednesday 13 January 1954), noted that probate had been granted to Thomas L. Winn, dental surgeon and Miss Gladys M. Winn.

A few years later, in November 1957, Leith’s brother, Kenneth, passed away, leaving his effects to his widow. There was no evidence that Kenneth and his wife had any children.

Leith himself passed away on 10 December 1964 at Charing Cross Hospital. While still a resident of Pevensey Bay, he had apparently been transferred back to London for medical care. In the latter stages of fibroid phthisis, Leith was probably subject to paroxysmal coughing upon arising in the morning. His coughs would have expelled fairly large quantities of “purulent expectoration of an offensive sputum”. Leith would have had trouble breathing and his health would have been greatly impaired. In the final stages of the disease, his other organs (heart, liver, kidneys) would have been affected. His was most likely not a pretty death. Leith left about £13,000 to his spinster sister, Gladys May Winn.

Although Leith played a relatively minor role in the case of German spy Josef Jakobs, the thread of his life is fascinating in its own right.

References

Air History website – info on John Hilton Winn.

British Army Lists – 1940 & 1941.

Groningen Camp Magazine website.

First World War website – info on Groningen Camp

Genealogy websites – Ancestry, FamilySearch – births, marriages, deaths, census, passenger lists.

London Gazette – 1940 & 1941.

Memorial of the Great War 1914-1918 – A Record of Service. Published by the Bank of Montreal. 1910.

National Archives – KV 2 files on Josef Jakobs, KV 2/1936 file on Nikolai Hansen & Admiralty (ADM) file on Thomas Leith Winn.

Stephens, R.W.G. – Camp 020:MI5 and the Nazi Spies (edited by Oliver Hoare). 2000.