A few years ago, I wrote a blog about the farewell letters of the executed spies in England.

Those letters, written by condemned men on the day/night preceding their execution, were to have been delivered to their families after the Second World War. They never were. The letters sat in the files of MI5 and, when these files were declassified in the late 1990s, most of the letters were included in the release of documents to the National Archives.

That has always perplexed me. Why could the letters not have been delivered? I might have found an answer.

I was poking around the Imperial War Museum website and came across this note on enemy property.

The Enemy Property Act extinguished all German interests, both copyright and ownership, in all material belonging to former German enemies (whether individuals or businesses) which was brought into the UK from certain territories between 3 September 1939 and 9 July 1951.

(from www.legislation.gov.uk – opens as a pdf)

The blurb refers to the Enemy Property Act 1953, a rather dense piece of legal jargon that is available on the internet in its entirety.

The Imperial War Museum’s blurb is far more readable and sums it up nicely. I had a peek in the original document to get clear on a few definitions.

The term “German enemies” can refer to the German state, a individual who is a German national, someone who is resident in Germany or in enemy territory or someone who for the time being is deemed to be an enemy for the purpose of the Act of 1939.

The term “enemy property” means “any property for the time being belonging to or held or managed on behalf of an enemy or an enemy subject, and for the purposes of this definition the expressions “enemy” and “enemy subject” have the same meanings as for the purposes of the Act of 1939.

Sooo… basically, any property that the spies brought over with them, whether personal items or espionage equipment, belongs to the United Kingdom. Whether this material sits in government files or museum archives, ownership by the individual was relinquished. I’m going to suggest that this likely also applies to the farewell letters. The letters were held on behalf of the enemy agents and as such technically qualify as “enemy property”. Legally, the government was quite within its rights to hold onto those farewell letters and release them to the National Archives. Morally… I’m not so sure.

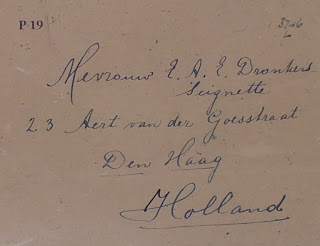

The farewell letter of Josef Jakobs is an exception as it was offered back to our family in the mid 1990s, but only because I had been searching for information on my grandfather. Perhaps if other families had searched, they too would have received their letters… at least before they were released to Kew.