My father, Raymond Jakobs, was the son of Josef Jakobs. Born in the early 1930s, my father didn’t really know his own father at all. Josef was either travelling or locked up in Swiss prisons or German concentration camps. My father was only 8 years old when Josef departed on his mission to England. Twenty years ago, I sat down with my father and interviewed him about his memories of growing up in wartime Berlin. It wasn’t a pleasant story.

There was one vignette from his life that has stuck with me over the years, the story of a young Jewish boy with whom my father used to play. I’ll let my father tell the story as I heard it from him.

Shortly after we moved to the Rudolstädter Straße [they moved there on 1 Oct 1938], I started playing with a boy, named Gerhard Drucker. He was a bit older than me, and taller and heavier. He wore thin, horn-rimmed glasses. We used to play together, and Regine (my sister) and I would go to his house. His father was a dentist and they lived in Sybelstraße. I could probably still find my way there today. His grandparents lived across the street, just a few doors down from us. We went to visit the grandparents one day and got a big surprise. His grandparents were Orthodox Jews! His grandfather wore black clothes with the big hat and everything in that apartment was dark, even the furniture. We went there once or twice, but I didn’t want to go back because it was so different and scary for me.

For a while, Gerhard didn’t come over to play, and I didn’t know what had happened to him. On the day he came back, he was holding his arm kind of funny across his chest. He said to me, “You know, we can’t play together anymore.” He moved his arm and showed me the Star of David that he had to wear on his sweater. He came over a few times after that, but we really couldn’t play with him. Had we played with him, my mother would have gotten into trouble with the Gestapo. You weren’t allowed to have any contact with anyone wearing a yellow star.

One night I had to go to the toilet, so I went out of the bedroom and across the hall. My mother was standing at the door with Gerhard’s grandfather. After he left, my mother called me over and said, “You will never say a word that this person was here or what happened.” It turns out, she was giving him food. As Jews, they couldn’t buy very much and didn’t get enough food stamps, if any. I think he came two or three times, but then, one day, the grandparents were gone. Later on, Gerhard and his parents all disappeared as well. I vaguely remember that they were trying to get to America. Early in the war, if a Jewish person had money, they could usually get passports or papers to leave the country, because the Nazis needed money. I think Gerhard and his family got away safely, except for the grandparents. They were just gone one night and were probably taken to a concentration camp.

(from the autobiography of Raymond Jakobs)

Lingering Questions

For years, I have wondered what became of Gerhard Drucker and his family. After discovering the 1939 German Minority Census, I decided to try and trace the family.

I began by looking for individuals named Drucker in Berlin, specifically any living on the Rudolstädter Straße and the Sybelstraße.

Druckers on Rudolstädter Str, Berlin

At Rudolstädter Straße 95, just down the street from where my father lived, we have:

- Benno Drucker – born 10.12.1899 in Bartin, Pommern

- Gert Drucker – born 5.2.1930 in Berlinchen, Soldin, Brandenburg

- Gustav Drucker – born 24.6.1874 in Flecken Gülzow, Cammin in Pommern

- Rosalie (née Rewald) Drucker – born 26.4.1873 in Bartin, Pommern

At Sybelstraße 65, we have:

- Adele (née Freundlich) Drucker – born 7.4.1904 in Lauenburg in. Pommern

- Jenny (née Boss) Freundlich – born 25.12.1877 in Karthaus, Westpreußen

Based on the information provided by my father, the individuals at Rudolstädter Straße 95 could very well be Gerhard Drucker (Gert is a common abbreviation of Gerhard), Gerhard’s father (Benno) and Gerhard’s grandparents (Gustav and Rosalie – 64/65 years old in 1938). The women living at Sybelstraße 65 could be Gerhard’s mother and maternal grandmother. This seemed a promising lead and I did some more digging and the more I found, the more convinced I was that this was indeed the Jewish boy with whom my father played. Gert wore thin-rimmed glasses, was two years older than my father and his father was a dentist. For me, it was enough to devote some time to tracing the family. I have good news and I have bad news. Benno and his parents, Gustav and Rosalie, were murdered in the Shoah. Gert, Adele and Jenny survived. This is their story told, in part, by Gert himself.

From Berlinchen to Berlin

Gert was born in Berlinchen (now Berlinek/Barlinek in northwestern Poland) on 5 February 1930. Gert’s father, Benno, was a respected dentist who had fought for Germany in the First World War and later studied at the Universität Berlin. Gert’s mother, Adele (née Freundlich) was a nurse.

(From Museo do Holocausto site)

Gert lived his early years in the small town of Berlinchen, nestled in a beautiful valley, surrounded by a lake. He loved spending time with his paternal grandparents, Gustav and Rosalie, who spoiled him.

In November 1938, during Kristallnacht, the Berlinchen synagogue was burned down by the Nazis who also destroyed Jewish shops and assaulted many Jews.

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, Gert’s father, Benno was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. The writing had been on the wall for a while given the restrictions imposed on the Jews by the Nazis. For months, Benno had only been allowed to see Jewish patients.

After Benno’s arrest, Gert’s mother sold the dental practice and took Gert (8 years old) to Berlin to live with Benno’s parents (Rudolstädter Straße 95) and Adele’s widowed mother (Sybelstraße 65). As a Jew, Gert was forbidden from going to the cinemas, regular schools or riding the trams. In early 1939, Benno was released from the concentration camp and rejoined his family.

The 1939 German Minority Census captures Benno and Gert living with Gert’s paternal grandparents and Adele living with Gert’s maternal grandmother. Gert would later say that the family was living with false documents, but this may have happened later since they are listed in the census under their real names During this period, some of the family’s inland relatives were deported to the Warsaw Ghetto in Poland. They would not survive.

Tragedy Strikes

On 26 August 1942, Gert’s paternal grandparents, Gustav and Rosalie were both arrested and transported to Theresienstadt concentration camp. They too would not survive. Gustav died on 4 February 1943 at Theresienstadt, a victim of pneumonia. Rosalie died eleven days later on 15 February, 1943, due to acute enteritis (inflammation of the intestines caused by eating contaminated food and liquid).

With the Nazi noose slowly tightening around the Jews, Gert’s parents decided to escape from Germany. While they were organizing the final details and arranging false papers, Gert related how the Gestapo had come to their building, looking for them. The family first fled to Belgium where Gert attended a Boy Scout camp. In the early months of 1943 the family arrived in the south of France, passing through Monaco, but they would not remain together for long.

(From USC Shoah Foundation site)

Benno and Adele were arrested and sent to work camps. Adele was sent to the Rivesaltes transit camp and then on to the Gurs internment camp, both at the foot of the Pyrenees.

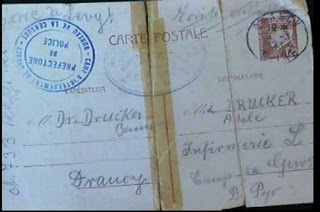

Benno was also sent to a work camp but, in March 1943, was among almost 2000 Jewish men selected for deportation in retaliation for the killing of two German Luftwaffe officers. Benno was sent to the Drancy transit camp near Paris and from there wrote a final post card to his wife at the Gurs camp. The post card was sent to the Infirmary at Gurs and it is likely, given that Adele was a nurse, that she was working in the infirmary. Her training and skills may have saved her from extermination. Benno was not so fortunate. He was sent to an extermination camp in Germany (sources vary: either Auschwitz, Majdanek or Sobibor). He was 44 years old.

As for 13 year old Gert, he was sent to an orphanage called Château du Masgelier in Creuse. Several groups in France organized themselves to save Jewish children by placing them in orphanages. While Gert would say that “Being separated from my parents was the end of the world for me”, it also saved his life. Gert and his mother exchanged letters until the end of the war. One can only imagine the anxiety and terror of mother and son, always wondering if each letter would be their last.

Escape to Brazil

(from Museo do Holocausto site)

After the war, Adele and Gert reunited and waited at the Chateau de Corbeville in Orsay, France, considering different possibilities for emigration. South Africa was high on the list as Adele’s mother had escaped there on 5 April 1940. The United States was also an option but, in the end, Brazil won out. A colleague of Benno’s had arrived in Brazil several years earlier and bought some properties. Another source suggests that, in 1938/1939, Benno himself had arranged to purchase some land in Blumenau, Brazil from a German who, when the war started, wanted to return to Germany.

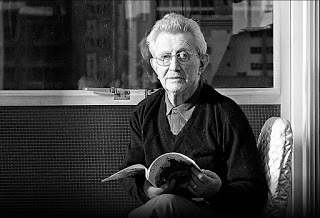

In 1946, Adele and Gert arrived in Blumenau, Brazil but would settle permanently in Curitiba. Gert learned Portuguese and continued his studies. For years he worked as a stamp dealer and later became a postmaster. His mother passed away in 1977. He went back to school later in life, studying at the Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná, and graduated as a psychologist, finding work with the Ministry of Labour until his retirement.

(from Museo do Holocausto site)

Gert would become a staunch ally of the Museo do Holocausto in Curitiba after it opened in 2011. He was also a Esperantist, a speaker of the most widely used “constructed” language, Esperanto. He even has an entry on Vikipedio, the Esperanto language site of Wikipedia.

For years, my father had hoped to track down his childhood friend, the Jewish boy who couldn’t play with him anymore. We searched in the USA, as my father thought that they might be trying to escape to America, but had no luck. But, every year, more information is released to the internet and, in this case, it was the Mapping the Lives site that gave me the break I needed. Too late on many fronts.

My father passed away in February 2019 and I never got the chance to tell him, “I found Gerhard!”. Gert himself passed away earlier this year in Curitiba after having celebrated his 90th birthday in February. I can imagine the two old friends having a reunion in the hereafter, sharing stories. They found each other.

Sources

Museo do Holocausto de Curitiba – article on Gert Drucker

USC Shoah Foundation – Visual History Archive Online – index and images of interview with Gert Drucker – index in English, interview in Portuguese and not available online

Museo do Holocausto – FB page – April 11, 2020 – Death notice for Gert Drucker with a photo

Gazeta do Povo – online Newspaper article about Gert Drucker

Vikipedio – Esperanto article on Gert Drucker

Ancestry – genealogical records

Mapping the Lives – site that has information on German Jews