While researching my book on Josef Jakobs, I necessarily delved into the files of the other LENA spies who were charged under the Treachery Act of 1940. The vast majority of spies who were brought to trial were convicted and executed by hanging. As I read the files, I became intrigued by the tactics used by the defence counsel. Some, like C.G.L. DuCann, defence counsel for Karel R. Richter, gave it a valiant effort and obviously devoted some thought to their defence. Others, however, seem to have done very little for their hapless clients.

I don’t know if it’s the media but… when I think of mounting a defence against a capital charge… I tend to think that the defence will have days, if not weeks to review the evidence. Maybe it’s just a modern thing? Or simply a figment of the fake world depicted in televised police dramas? The reality for many of the German spies was, to be honest, quite appalling.

Charged with Treachery

Let’s take the case of Werner Walti and Karl Theodor Drücke. The two men landed on the Banffshire coast in the fall of 1940, accompanied by a woman who was known as Vera Eriksen… or Vera de Schalburg… or a number of other versions of Vera. Drücke and Eriksen were snatched up at the Port Gordon railway station the morning of their arrival. Walti escaped notice for a while longer, managing to catch a train from Buckie to Edinburgh where he was ultimately nabbed by the police.

After being interrogated for months at Camp 020, Walti and Drücke were taken to Bow Street Magistrates’ Court where they were formally charged under the Treachery Act. Various witnesses gave their testimony at the deposition and the hapless spies were asked if they wished to add anything. Both were mute, likely understanding very little of the evidence given by the witnesses in their thick Scottish brogues. There is no evidence that either man had legal counsel, and no evidence that they were offered one for their future trial.

(National Archives KV 2/1704)

Several weeks later, on 12 June, 1941, the two men were brought to trial before Justice (Baron) Cyril Asquith and a jury (KV 2/1704). The indictment was read out to the accused and both men were asked how they pled, the answer to which, in both instances was “Not guilty”. There then followed a rather perplexing exchange:

Note: Drücke’s name was spelled incorrectly throughout the transcript as Drueke.

Clerk of the Court – Drueke [sic], have you anyone appearing for you?

Drueke – I do not understand.

Clerk – Have you any barrister appearing for you in this Court?

Drueke – No, I have not.

Clerk – Have you, Walti?

Walti – No, Sir.

Clerk – Do you both understand English?

Drueke – Yes

Walti – Yes

Clerk – Do you understand it sufficiently well to follow the proceedings?

Drueke – Not quite

It would appear that the Clerk of the Court was quite prepared to move the proceedings forward without either man being represented by counsel. Apparently I’m not the only one who thought that was a bit odd.

(From Wikipedia)

Justice Asquith – This is a trial at which the accused are apparently unrepresented by counsel. That seems to be very unsatisfactory.

Solicitor General – I agree (The Solicitor General, Sir William Jowitt was serving as the Prosecution during this trial.).

Justice Asquith – I think that they ought to be given the opportunity of instructing counsel; and I suppose that must necessarily involve the adjourning of the case, although not necessarily for long. It is very unfortunate.

Solicitor General – I should have thought that it would be convenient if we adjourned now, and started again after the luncheon adjournment.

Justice Asquith – How long will this case take: two days?

Solicitor General – I should think so. I must be some time in the opening, because I have to let the jury know what the exhibits are; but after I have done that the period of controversy will be very small indeed. The best way may be to have some counsel here to hear the opening and so get to know the facts, and then adjourn until tomorrow morning.

So the Solicitor General is advocating that the defence counsel only needs a few hours to become acquainted with the facts of the case? That seems rather brief.

The Clerk then asked if they had money, Drueke had nothing, Walti had 1 shilling.

Solicitor General – Of course, these men came to this country, and they had money. Indeed, a bundle of notes is one of the exhibits.

Justice Asquith – That has been impounded, has not it?

Solicitor General – It is physically here in this court, my Lord.

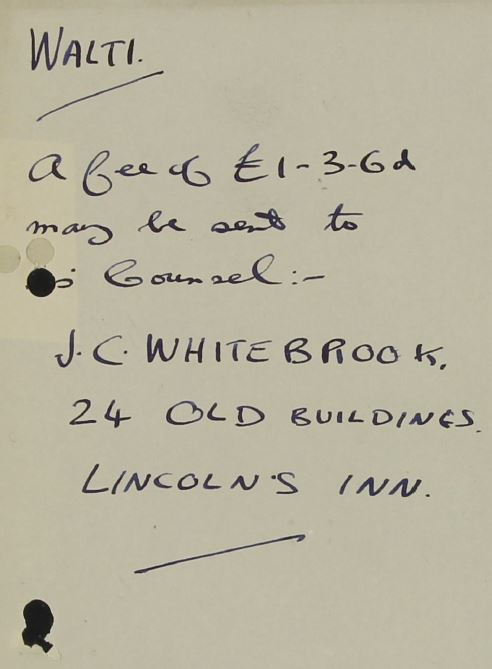

It would appear that the court decided to dip into the confiscated funds in order to pay for two barristers. Each barrister would receive a grand total of £1 3s. 5d.

(National Archives KV 2/1701)

After a short time (how short of a time is not noted in the trial transcript)

Clerk of the Court – Drueke, if you like to make a choice of the two counsel at the back there, you may have one to defend you. Will you pick one of them?

Drueke selected Mr. H.B. Figg (Hubert B. Figg)

Clerk – Walti, your choice is limited to the remaining member of the bar. Are you content?

Walti – Yes, sir.

Clerk – That is Mr. Whitebrook

This seems most unsatisfactory. Walti, going second was left with no choice – “choice = an act of selecting or making a decision when faced with two or more possibilities”. After Drücke’s selection, Walti was left with a “choice” between Whitebrook or Whitebrook. One would think that the court would have arranged to have at least three barristers available so that there was at least some validity to the word “choice”.

Justice Asquith – to Figg and Whitebrook – You wish to consult with your clients. This case will not be taken until two o’clock. I think that the Solicitor General’s opening will take most of the afternoon, and therefore you will have the evening and the night if necessary in which to fortify yourselves.

Sol. Gen. – I think it would be better if I have five minutes with my learned friends and tell them about the documents and so on.

(After a short time)

So the defence counsel had five minutes to hear about the documents, but likely no time to read them. They would have no time to come up with questions with which to cross-examine the witnesses.

The 12 members of the jury were then sworn. According to the transcript, both barristers had spoken to their clients and thought that they understood English quite well. Although, the court did take the precaution of swearing an interpreter but no name was given. The Solicitor General then gave the opening speech for the prosecution after which the first witness, John Donald (stationmaster at Port Gordon railway station), was called and sworn. Drücke’s counsel was able to cross-examine Figg but afterwards, the trial was adjourned to the next morning.

The trial continued the following day, Friday, June 13, with the remainder of the witnesses. Both barristers attempted to cross-examine the witnesses, but their efforts weren’t all that impressive. In reading the witness statements and some other documents, there appear to be several instances where the witnesses perjured themselves: (a) how many men actually grabbed Walti at the railway station and (b) how they opened his suitcase. Perhaps not earth-shattering bits of testimony but it does leave one wondering as to the accuracy of their assertion that Walti had tried to pull his gun out of his trouser pocket. More on that in a future blog post…

After hearing from the witnesses and the defence (only Walti testified), the trial was adjourned for the weekend, reconvening on Monday, June 16. The trial transcript notes that both Figg, Whitebrook and the Solicitor General gave summary statements to the court, but they are not contained within the document (KV 2/1704). Justice Asquith gave his summing up and the jury retired to consider their verdict. Not surprisingly, both men were found guilty on both counts (treachery and conspiracy).

Clerk – Prisoners at the Bar, you severally stand convicted of treachery. Have you or either of you anything to say why the Court should not give you judgment of death according to law?

Drueke – no

Walti – I should like to make an appeal.

(National Archives KV 2/1705)

An Appeal for Justice

Given that the two men were found guilty on 16 June, 1941, the legal process seems to have moved at a snail’s pace. Both Figg and Whitebrook appeared before the Court of Criminal Appeal on 21 July, 1941, more than a month after the trial.

Before The Lord Chief Justice of England Wales (Viscount Caldecote of Bristol), Mr. Justice Tucker and Mr. Justice Oliver, both barristers sought to deflect the sword of justice from their clients. Figg attempted to argue that there was no evidence supporting the charge of “conspiracy”. His appeal was dismissed.

As for Whitebrook, he apparently attempted an argument that left the three justices a bit bewildered.

With reference to the case of Walti, an argument has been advanced to us which is, in my judgment, almost incapable of statement. It is that inasmuch as the proper inference from the facts is that Walti was a spy, he had acquired a status which in some way or other, which I do not properly understand, enables him to avoid any liability under the Treachery Act. It is said that as a member of the belligerent forces of the enemy, that is to say of a foreign power, he might have been dealt with my what is called military law, and that by reason of certain Conventions entered into between this country and the enemy, and before the outbreak of war, Walti was incapable of being charged with an offence under section 1 of the Treachery Act. It is sufficient to say in answer to that submission that Walti’s case comes in terms, upon the view which the Jury took, within the language of section 1 of the Act. The two counts in the indictment follow precisely the language of section 1, which reads: “If, with intent to help the enemy, any person does, or attempts or conspires with any other person to do, any act which is designed or likely to give assistance to the naval, military or air operations of the enemy, to impede such operations of His Majesty’s forces, or to endanger life, he shall be guilty of felony and shall on conviction suffer death”. If it is suggested that that section does not in terms apply to a man who, it is suggested, belongs to the armed forces of the enemy, it is sufficient to point to sub-section (1)(c) of section 2, which provides: “if upon representations made to him, it appears to the Secretary of State that any person sentenced to death after being convicted on indictment of an offence against this Act was, at the time of the commission of the offence, a member of the armed forces of the Crown or of the armed forces of any foreign power, including an enemy power, the Secretary of State may direct that, instead of being dealt with in like manner as a person sentenced to death after being convicted on indictment of murder”, that is to say, hanged. Mr. Whitebrook, in his address, has put the only possibly argument which seems to be capable to being put in the case of Walti, and in his case also we think there is no ground upon which leave to appeal should be given to him.

What was Whitebrook’s appeal that left the justices perplexed? We need to delve into some subsequent documents to try and piece things together.

Further Appeals

On 1 August, 1941, a letter was sent to Sir Ernley Blackwell by someone whose signature is indecipherable. The only Ernley Blackwell, I could find, had served as Legal Assistant Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office from 1913 to 1933. He would have been 72 in 1940, and it is possible that he was consulted on various legal matters after the advent of war. In this letter to Blackwell, the unknown writer notes that:

“Mr. Whitebrook, Walti’s Counsel, telephoned this morning to ask if he could see Sir Alexander Maxwell [Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department] about the case. He has had Sir Alexander’s reply to the Memorial which he put in last week but he now feels that he would not be discharging his duty as Counsel if he did not draw attention to the fact that the Judge had said that it was unsatisfactory that the prisoners were not represented by Counsel either at the beginning of the trial or when the depositions were taken. He pressed to be allowed to see someone here on the ground that if he merely wrote his representations would not be fully considered. I assured him that this was not the case and added that if it appeared from his written representations that it would be useful for the appropriate officers here to see him they would of course get in touch with him. I held out no hope that anyone would feel it necessary to see him. (HO 144 21636)

Well, Whitebrook was on the ball. He too thought that it was rather unsatisfactory that his client (and Drücke) had not been represented by counsel at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, nor at the start of the trial. The Memorial that is mentioned makes some interesting arguments and we’ll consider those below.

A few days later, Whitebrook wrote a letter to the Under-Secretary of State (presumably Maxwell) regarding the Walti case.

Dear Sir,

It is with great reluctance that I venture to approach you again with a request to consider various features of the case of Walti, one or other, or the combined effect of which, might justify you in recommending a mitigation of the sentence.

He was, as you are aware, unrepresented at the Police Court, and I had no opportunity to see the Depositions, save as they were passed to me whilst the witnesses were giving evidence at the trial. Before the Magistrate, Walti could not have understood those witnesses, who spoke excellent English, with an accent [Scottish] difficult for a Southerner to understand. To cross-examine them was utterly beyond Walti’s power. The porter at Waverley Station was not cross-examined upon the matter of the revolver, whereon his evidence at the trial proved of great value to the Defence. The porter at Buckie was not questioned concerning the abandonment of the suitcase for three hours, unattended on the Station platform, in the hope that it would not accompany the unhappy holder further. The hasty instructions had not informed me of the incident. This fact, if elucidated, would, perhaps, have turned the balance of the Jury’s decision to accept the prisoner’s account of his motives. [As with most espionage cases, the spy was often portrayed as being a liar, and therefore nothing he said in his defence was of value.]

The absence of legal aid, at the Police Court proceedings, of a proper brief, duly prepared by a careful solicitor, of time to weigh the course of cross-examination, and of study to determine the legal status of the accused, with reference to the allegiance and the King’s Peace, all weighed against the prisoner. In the words of the learned Judge, “it was most unfortunate”.

The result was the presentation of the case piecemeal, part of the facts to the Jury, part, of which the Jury never heard, to you, part of the legal argument to the Court of Criminal appeal, and part, afterwards perceived by Sergeant Sullivan, to no-one. If, upon the grounds of his learned and experienced discrimination, the law should be determined in the light that I believe true, and applicable to Walti, at some future time, when he can no longer profit by a legal contention, it would be, indeed, unfortunate, that the course of hearing his case should have delayed the presentation of that legal argument to a date later than his trial. [Basically, had Whitebrook had more time to peruse the evidence and the depositions, he likely could have mounted a more vigorous defence at Walti’s trial.]

Bearing in mind the possible truth of the prisoner’s account, of the possible doubt as to the point of Law involved, of the utter valuelessness of the execution, which could not deter Hitler from sending a hundred like him to a similar risk, and of the desirability of exalting always the ideals of Justice to the most undeserving of God’s Creatures, I do venture this appeal to you.

Yours faithfully,

J.C. Whitebrook (HO 144 21636)

It isn’t clear to me if any of this was included in Whitebrook’s submission to the Court of Criminal Appeal, although the justices made no mention of Walti’s lack of access to counsel for the deposition or trial.

The Hague Convention and Spies

Whitebrook’s case to the Court of Criminal Appeal seems to have centred around The Hague Convention and its treatment of spies. We now come to the crux of the Memorial that was referenced earlier. On 24 July, a few days after the appeal was dismissed, Whitebrook wrote a letter to the Secretary of State (Home Office), likely Samuel Hoare. Whitebrook hand-delivered the letter on 25 July.

Dear Sir,

I beg to enclose herewith a memorial, putting forward what remains to be said on behalf of Werner Heinrich Walti, after the rejection of his appeal against sentence of Death on July 21st.

That the Memorial is very badly typed is due to the fact that the trial is secret, and that I could not let anyone but myself effect the work. I have not argued the difficulty of trying a Swiss by Court Martial, since I believe that ample precedent exists.

If anything were to be added to the Appeal, it would be that the tale of Walti is possibly true, that he is a very young man, of apparently poor instincts, apart from this offence and that he effected no known harm. He might serve, if his life were in being, as a person to be shot should reprisals ever become necessary.

The arguments apply, so far as I can perceive, without reservation to his collaborator, whom I do not represent. This man is an Enemy Alien, and could have been tried by Court Martial without any manner of doubt.

Whilst seeking pardon for any bluntness of putting these contentions, due to my inexperience of procedure in such cases, I would beg you to believe me, with every expression of respect.

Your Obedient Servant,

J.C. Whitebrook, Barrister (HO 144 21636)

The memorial follows:

Memorial Relative to the Case of W.H. Walti, Now Under Sentence of Death (Treachery)

It is represented, upon behalf of the Prisoner, that, whereas, under Section 4(b) of the Treachery Act, provision is made, for the trial, under that Act, of persons subject to military law, that he, as a spy, or a person convicted of having acted in such capacity, has, in the said military law, a defined status.

Upon Appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal, on July 21st, it appeared that the rights arising from such status do no appertain to persons, but are agreed rights between covenanting nations, and that such rights of status as arise under Sections 29 and 31 of the Annex to the Hague Convention of 1907 (ratified by Great Britain in 1909) and entitled the “Laws and Customs of War”, and sub-titled “Spies” could not be considered by the Court.

Nevertheless, it is submitted that, as obligations, into which His Majesty’s Government has entered, the rights and status accorded to Spies, whether of Enemy Powers, or of Neutrals acting as agents of Enemy Powers, should be recognized strictly, in accord with the provisions of the Hague Convention, and that, whilst such recognition would be accorded by a Court Martial, the recognition in the case of a Civil Trial can be procured only by the act of the Executive; that is to say of His Majesty’s Secretary of State.

The rights before-mentioned forbid the treatment of a Spy as a felon. For example, Section 31provides that if an escaped Spy rejoins his army, he shall not, on recapture, be tried or punished for his former espionage. The exact reverse is the case with felony.

Section 441, Chapter XIV, Manual of Military Law, points out that the acts of a Spy are not touched with moral taint, and may be praiseworthy and patriotic; the reverse is true of Felony and Treachery (which receive commendation in no official text-book) wherein always is baseness, the mens rea of the crime.

Since it is desirable that the rules of War, afore-cited, should be observed strictly by all belligerents, and since His Majesty’s Government appears pledged to this effect, it is urged that even had the prisoners effected harm punishable with death, by military law, the death of either, as a felon, would violate letter and spirit of International Obligations, and should not be permitted.

It is further represented that Walti falls under the head of Enemy Alien, despite Nationality. the incorporation of neutrals among belligerents. Section 475 ibid. Walti was under ties of local allegiance in two Enemy occupied countries, and in Germany itself, before he accepted a charge which actually placed him on an Enemy vessel with duties imposed on him under the charge. He falls, therefore, under the Hague Rules, applicable without distinction to all spies, save those, subjects of one of the belligerents who commits Treason, Treachery, or War Treason. Paras 166. 167 ibid. Into the question of visitors, raised by those paras, it is, fortunately, not necessary to enter, since the act laid in the Indictment is landing.

The argument that I have propounded leads to the result that, if the Section of the Hague Convention quoted is accepted, then Walti, not a felon, is no longer triable by Court Martial, since he could plead autrefois convict (a defendant’s plea stating that he or she has already been tried for and convicted of the same offence). Nevertheless he remains a War Prisoner, liable to be chosen for the purpose of any reprisals, at any time necessary.

On the point of Conspiracy, it is pointed out that if Walti’s companion were held not a felon, on the grounds shewn, that the charge of Conspiracy against Walti fails also, since a man cannot be found guilty of feloniously conspiring with himself.

Walti desires me to add his respectful request for the form of Death, if these arguments prove unavailing, to be Shooting, and points out that at the landing he was an active member of the crew of a boat attached to an enemy vessel of War, and, therefore, at least at some time, a member of the armed forces of the Enemy.

J.C. Whitebrook (HO 144 21636)

(National Archives KV 2/1701)

Well, that’s an intriguing argument. Essentially, as a spy for a belligerent foreign power, Walti should have been tried by court martial, not tried as a felon by civil court. But, given that he has already been tried by a civil court (and found guilty), then he could not be tried again, by court martial, for the same offence. Even Walti himself noted that he had been an active member of an enemy vessel and should have been considered to be a member of the enemy’s armed forces. Interesting. Someone (the signature is not clear) reviewed Whitebrook’s argument and had this to say on 28 July:

I have looked at the articles of the Hague Convention and the paragraphs of the Manual of Military Law to which Mr. Whitebrook refers but I find his arguments difficult to follow.

His first argument appears to be something like this. The provisions of the Hague Convention imply that a spy is not to be treated as a felon. Walti is a spy within the meaning of the article in the Hague Convention, therefore, though he might have been sentenced to death by shooting by a Military Court for a war crime he ought not to have been convicted of felony and sentenced to be hanged under the Treachery Act.

A spy is defined in Article 29 of the Hague Convention as a person who “acting clandestinely or on false pretences… obtains or endeavours to obtain information in the zone of operations of a belligerent with the intention of communicating it to the hostile party”. Whether Walti falls within this definition I do not know, but in any case I can see nothing in the Hague Convention which in the words of Mr. Whitebrook “forbids the treatment of a spy as a felon”. Article 31 to which he refers says “a spy who after rejoining the army to which he belongs is subsequently captured by the enemy is treated as a prisoner of war and incurs no responsibility for his previous acts as a spy”. This is a humane provision to secure that if a soldier who has acted as a spy gets back to his lines and is subsequently captured as an ordinary prisoner of war he would not then be shot as a spy. To build on this provision a doctrine that a spy can never be treated as though he were a felon seems very far fetched, apart from the consideration that the provision about “rejoining the army to which he belongs” hardly seems appropriate to Walti, who according to his own story refused to join the Germany army.

The second argument appears to be that Walti is a spy within the meaning of the Hague Convention because he is an enemy alien despite the fact that he himself says he is of Swiss nationality and lived in Belgium. In support of this argument Mr. Whitebrook refers to Section 475 of the Manual of Military Law which says: “The duty of neutrality does not compel neutral states to take measures to prevent their subjects from joining the military service of a belligerent”. But even assuming there is nothing in the Swiss law to prevent Walti joining the German army the argument seems quite irrelevant to the point at issue.

Indeed if there were anything in Mr. Whitebrook’s point I think it would be that the British Government contravened the Hague Convention by allowing Parliament to pass the Treachery Act of 1940 in such a form as to render liable to a conviction of “felony” persons who may be spies within the meaning of the Hague Convention.

unclear signature (HO 144 21636)

Soooo… if I’m reading this right, the author is admitting that, in passing the Treachery Act of 1940, the British Parliament contravened The Hague Convention (1907). Fascinating. And a very astute legal argument by Whitebrook. Clearly, he devoted quite a bit of thought and research into his post-trial defence of Walti.

Even though Whitebrook’s attempts failed, Walti himself was grateful. On 5 August (the day before his execution), Walti wrote a letter to Whitebrook from Wandsworth Prison. He acknowledged that the Attorney General had refused his certificate on 31 July, 1941, and noted: “It is my sincere wish to express you my gratitude for all your efforts on my behalf” (KV 2/1705)

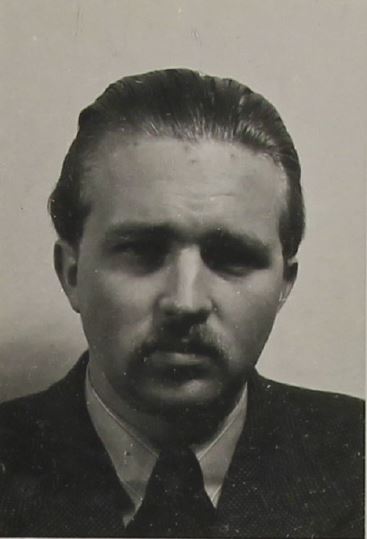

I am always fascinated by these stories. Who was J.C. Whitebrook? What had shaped this man so that he gave his best in service of a German spy? The story of Whitebrook is convoluted to say the least!

Sources

National Archives – KV, HO and CRIM files on Walti & Drücke

Header image from Pixabay

Hi Giselle,

For years now I have been trying to establish Werner Heinrich Wälti’s real identity. But I’ve had no luck with the National Archives in Kew, the Swiss National Archives in Bern or in correspondence with German archives. Two possible names that appear are Petter and Keller, but they don’t help with the search.

I’d be grateful for any pointers!

Thank you.

Hi Peter! Thanks for the comment and sorry for the delayed response. Yes, Werner is a bit of a conundrum. I have come across the Petter name before but it just seemed to fizzle out. Not sure about the Keller name. Whoever he was, he covered his tracks very well and it’s unfortunate that the German archives don’t have anything on him. What about Norwegian archives? Given that their mission originated there… it’s a (slim) possibility.

Let me know if you come across anything definitive! And I’ll do the same!

P.S. How about the Dutch archives? Given that they spent time in Holland before their mission. It would be a long shot as well and might just yield his “Werner Heinrich Wälti name. But… worth a shot?