N.B. This is Part 2 of a 5-part series on H. Ely Goldsmith. Part 1 can be viewed here. Links to the other parts are at the bottom of this post.

Introduction

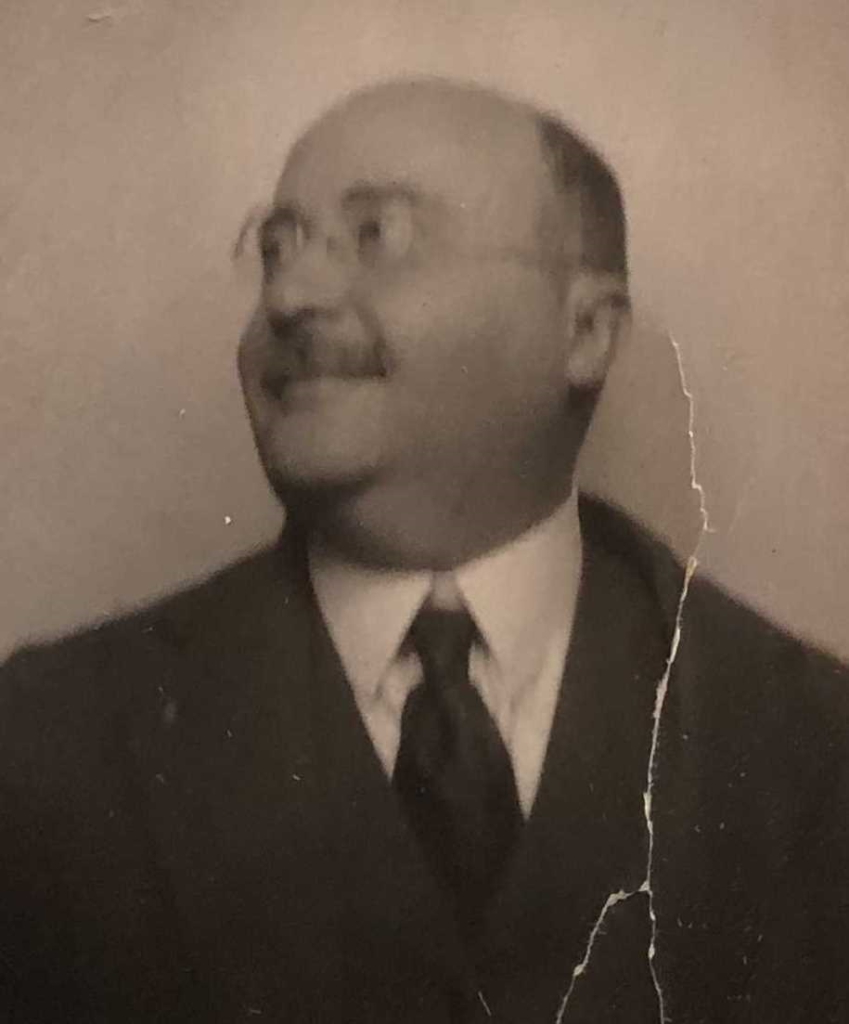

Ely Goldsmith seemingly had it made, carving out a new life for himself in the USA. He was a naturalized citizen. He was married with a beautiful daughter. He was a Certified Public Accountant and had a burgeoning business, Accurate Audit Co. And yet, as the new decade dawned, Ely began to go off the beaten path. He started to help aliens with visa requirements, something he wasn’t qualified to do. He expanded the scope of his accounting firm to counsel resident and non-resident aliens on income tax laws. He wrote articles for trade journals, placed provocative ads in American and international newspapers, and began to avail himself of the American legal system, bringing case after case before the courts.

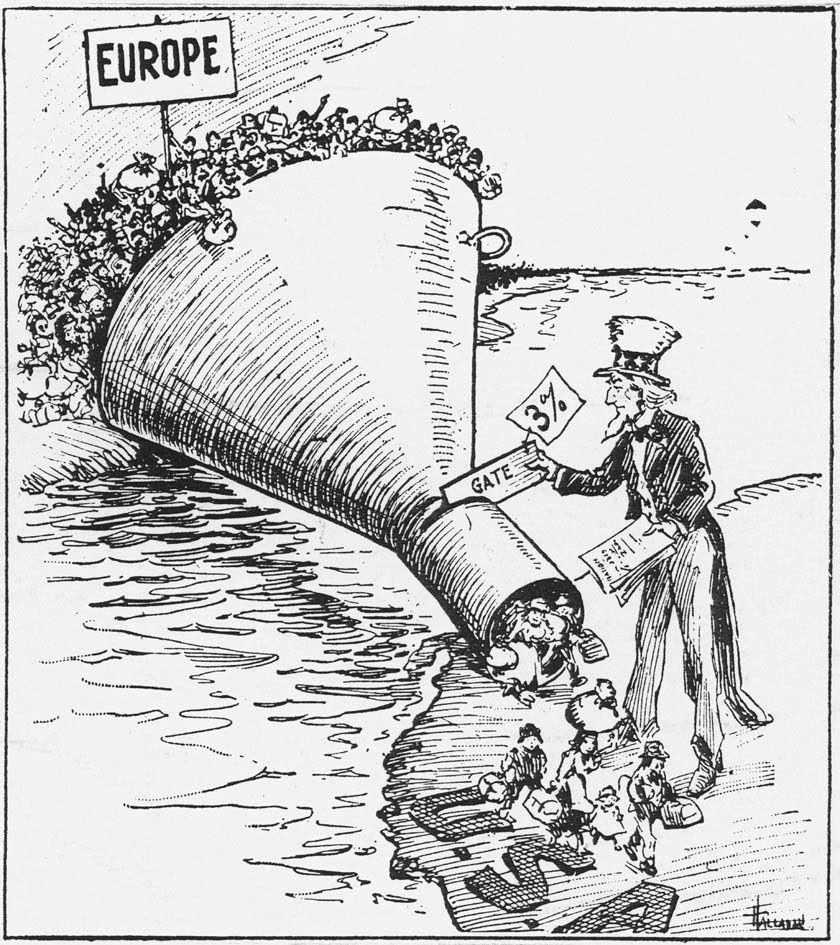

The early 1920s also marked America’s ever-tightening regulations against immigrants from certain “undesirable” races and ethnicities. First in 1921, and then in 1924, the American welcome mat became smaller and smaller. Italians need not apply. Nor Eastern Europeans. Nor Jews. This was the time of immigration quotas and these quotas were based on extremely racist theories. And yet, in the aftermath of the First World War, there were thousands upon thousands of displaced persons in Europe (many from the eastern regions) who sought to find some way, any way, to enter America, legally or not. Ely was more than happy to help them find a crack in the system. But first… we have to wonder why Ely began tilting at various legal windmills with wild abandon.

Ely’s Crusade Against Injustices

I wonder how deeply Ely’s experience at the Board of Education shaped his character. According to the Special Agent, Ely took the Board of Education to court and won. I haven’t been able to find any record of him definitively winning the case, but I get the sense that Ely’s crusade against injustice may have had roots in that experience.

On 17 July, 1921, Ely brought a case before the courts, arguing that gambling losses should be considered tax deductions. It’s rather an eye-popping argument and apparently the lower court gave the case short shrift. Ely then took the case to the Supreme Court of New York where he actually convinced one of the justices that “if gambling winnings were taxable, then gambling losses should be a deduction”. Kind of like business income and expenses, I suppose, although one could hardly claim that “gambling” was a business. In fact, the State Controller argued that since gambling was prohibited by the Penal Code, gambling losses could not be considered a legal ground for income deductions. The Supreme Court ruled against Ely (notwithstanding the one dissenting opinion) but he did not let it rest. The lower court had ruled against him. The Supreme Court had ruled against him. He took his gripe to the Court of Appeal which heard the case in early 1922. They didn’t even bother to issue a legal opinion on the ins and outs of the case. They simply confirmed the Supreme Court ruling. Gambling losses were NOT tax deductions. Courts 1, Ely 0.

A few months later, on 1 June, 1922, Ely brought a legal case against the Jewish Press Publishing Co. This case appeared before the Supreme Court of New York, and in this instance, Ely was represented by a lawyer – Dennis Buhler Woodward. What was his complaint against the Jewish Press? Well, apparently they were running advertisements from five individuals who falsely claimed to be “CPAs” or “Certified Public Accountants”. Ely had notified the publisher of these misleading advertisements and yet the Jewish Press continued to run these patently misleading ads. The injustice of it all must have rankled. Ely had worked hard to become a CPA and here were these fraudsters claiming to be the same, potentially stealing business and clients from him. In the end, however, the court ruled that while there might be a misdemeanor somewhere in the case, that would be for the criminal courts to handle. On top of that, Ely had produced no evidence to demonstrate that these ads were actually hurting his business. The case was dismissed. This must have left a bitter taste in Ely’s mouth. The unfairness of it all. The injustice. These fraudsters were getting away with lying. Courts 2, Ely 0.

A few months later, our clever little fellow picked up a taxation gauntlet. On 11 November, 1922, the NYT ran an article which originated with our friend Ely. According to the article, the Treasury Department had issued a new ruling which required “every taxpayer carrying on the business of producing, manufacturing and selling any commodities or merchandise” to keep permanent books of account or records. With the exception of farmers… who did not need to keep permanent books of account. Ely bristled at the injustice: “Other business men are put to a distinct and unwarranted disadvantage by the regulation which allows the farmer to escape investigation of his tax liability while the manufacturer and other business men are kept to a strict accountability.” Men like Ely, presumably. Having lost two court cases, Ely took his gripes to the press and public opinion.

All of this makes me wonder how well Ely was doing in terms of his accounting business. His offices had been at 1265 Broadway for several years, but by 1922 he had moved several blocks north to 105 West 40th Street. While Ely grumbled about the false ads of others, he also ran ads. One such ad in the 1 Feb, 1923, edition of Variety stated:

I can prepare and file your returns even when you are not in New York. Write me about your circumstances and I will ask you for such details as I need.

Given what we know of Ely’s penchant for handling the tax affairs of resident and non-resident aliens, we can read between the lines and see the type of clients he is seeking to attract. People who might live abroad and who needed help filing tax returns. And who might need help with a few other things… like visas and passports.

Post-War Visas

In the years following the First World War, travel between countries and continents began to resume. Released from the horrors of war, which had forbade many from visiting family in “enemy” nations, people now wanted to travel. This desire for travel resulted in some streamlining of travel documentation. In 1920, the League of Nations adopted the standard booklet-style passport that we still use today. Many European countries dropped visa (visé) requirements, a process that was similar to the old saying: “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine”. If Germany no longer required visas for British citizens, then Britain would happily return the favour and waive visas for German citizens.

One of main outliers to this genial visa-waiver reciprocity was the USA which still required foreign nationals to acquire a visa and pay the required fee. European nations retaliated by requiring US citizens to acquire a visa prior to visiting their country. This could lead to very high costs if, for example, a family of 4 wanted to travel from Italy, through Austria, to Germany and then Holland. Four countries would each require the payment of a visa… the costs added up quickly.

On 19 February, 1925, the House of Representatives was engaged in a debate of the visa issue and several letters, news articles and other correspondence were read out to the members. One of the letters was from our friend Ely. I include it in its entirety here because it gives us a sense of the man, his education and his eloquence:

The next communication is from Mr. H. Ely Goldsmith, a certified public accountant of New York City, and head of the Accurate Audit Co. of that city. On September 23, 1924, Mr. Goldsmith said:

Editor New York Times, Times Building, New York, N.Y.

Dear Sir: For a proper understanding of the passport-reform question mentioned in the statement of Congressman Bloom in the Sundays Times and in a letter by Mr. Shepard and another published in Monday’s Times it is necessary to realize the background for all these complaints.

The difficulty Americans are suffering under is not so much the fee charged them for a passport by the State Department, but the fee charged for a visé [visa] to foreigners attempting to enter the country. This visé charge being unreasonably high, it leads to retaliation on the part of all foreign governments.

The charge had its origin during the war, when the Secretary of State’s office came to the conclusion that the foreign service of the United States had to be made nearly self-supporting in order to induce Congress to provide the Department of State with adequate appropriations for the support of the foreign service, and therefore it asked Congress to pass laws providing for such revenue as was calculated to raise sufficient funds. The expense falling to the greater extent upon foreigners, Congress had no misgiving about enacting such laws. (Foreigners don’t vote here.)

However, Congress overlooked that this is a game that two can play at, and the foreign governments saw a chance to get back at Americans, and they did it in a manner outlined by the various parties whose communications the New York Times recently printed.

There is no more reason why the foreign service or the Immigration Service should be self-supporting than that the Attorney General’s office or the Weather Bureau should be self-supporting. They are all parts of the general scheme of government, every service doing its allotted share for the benefit of all citizens, and every one of them can and should be supported principally by general taxation as distinguished from a special tax or free on those using the service.

I have no figures showing the amounts collected by the department from the visé fees, but they can not possibly equal the amount paid by individual Americans as similar fees to foreign governments. It seems, therefore, that the most necessary remedy is the abolishment of the visé charges as against those countries who will reciprocate.

As to the charge made for issuing a passport, I am not so certain whether that is unreasonable, because it is a special service rendered to some citizens which other citizens do not ask for.

If Congress feels that the expense of the foreign service should be paid for by citizens traveling abroad, I believe it would be wiser to even increase the passport fee rather than continue the visé fee as at present. But to my mind even that is unnecessary. The fee of $1 or $2, as charged before the war, is amply sufficient for the clerical service, and if citizens’ protection by the Government while abroad must be bought a more adequate payment should be exacted.

Congress should provide liberally for the foreign service in every respect, as that service is of great help to the country at large, but it should not require a small percentage of Americans to suffer intensely in expenditure by money, time and patience because it wants to load upon the foreigners part of the expense of that service.

H. Ely Goldsmith

Certified Public Accountant, State of New York

The year 1925 seems to be the turning point for Ely. While he had certainly started his mad tilt at various legal windmills prior to that year, it was in 1925, that things really start to take off. Ely began to regularly appear in various newspaper articles and court appeals. Not always for the best reasons.

Expanding his Reach

In March 1925, Ely appeared before the Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia (DC). He had apparently applied to the United States Board of Tax Appeals to be enrolled as an attorney. The Board was created in 1924 and had quasi-judicial privileges to conduct tax appeal hearings with a quasi-judicial character. Ely had applied to be recognized as an “agent” or “attorney” (presumably quasi-judicial) who could appear before the Board and advocate for his clients during their tax appeals. The Board of Tax Appeals had sent his application to a commission which had “received, considered and denied” his application. Rather than request a hearing from the Board at which he could argue his case, Ely simply filed an appeal with the Court of Appeals. According to him, the Board’s denial was arbitrary and “capricious”. The Board of Tax Appeals, for their part, had submitted a response to the Court of Appeals which stated that their unanimous decision was:

“… based upon the judgment and determination that the petitioner [appellant] is lacking in integrity, is of bad character and reputation, is untrustworthy, and is unworthy of the confidence necessarily imposed by any judicial, quasi judicial, or administrative body of the government in practitioners appearing before it to represent taxpayers or clients.”

Wow. That is quite the departure from the Special Agent’s assessment in 1920. He had concluded that Ely enjoyed a good reputation, both personally and professionally. What could possibly have happened in the intervening five years for the Board of Tax Appeals to reject Ely with such a damning judgement?

Luckily for us, the Board of Tax Appeals presented two key points that informed, and supported their decision to reject his application.

In the first point, according to the Board, Ely had been discharged from a position in the comptroller’s office of the state of New York for alleged violation of the duties of his position. This is likely the issue Ely had had with the Board of Education between 1915 and 1920. The Special Agent in 1920 had noted that Ely had taken the Board of Education to court and had been vindicated. Right? Nope. Wrong. The Board of Tax Appeals noted that Ely had applied to the courts to force the Board of Education to reinstate him. But all the courts of the state had decided against him. I take this to mean that the initial court decision went against him, and then the court of appeals, and then the supreme court of NY. This is most decidedly not what Ely told the Special Agent who interviewed him for his passport application in 1920. From the information provided by the Board of Tax Appeals, it would appear that Ely had lost his battled with the Board of Education.

The second point that the Board of Tax Appeals used to support their decision against Ely was a bit was simpler. Ely had also applied to the Secretary of the Treasury to be enrolled as an accountant or agent to represent others before the Treasury Department. That application had ultimately been refused, primarily because charges had been brought against Ely by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. And if the Secretary of the Treasury had rejected Ely, then obviously, the Board of Tax Appeals would reject him as well.

Ely’s eloquent response to the Board of Tax Appeals was simple. Everything they presented was “at best hearsay evidence”.

The Court of Appeals denied Ely’s petition to reverse the Board of Tax Appeals decision. But Ely was a clever, little fellow and he naturally pursued every legal avenue open to him, and submitted an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nothing if not tenacious. After all the tortuous appeals and counter appeals, the Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Ely should have appealed the initial refusal to the Board of Tax Appeals, and demanded a hearing. He chose not to do that, and instead went directly to the courts, thereby shooting himself in the foot. His appeal was denied on 1 March 1926. Courts 5 (6?), Ely 0.

On top of his appeal to the Board of Tax Appeals (DC), he also applied to the Board of Accountancy in DC to be admitted as an agent or accountant and was denied there. He took them to court as well and after the judgments went against him, submitted various appeals to higher courts. The Court of Appeals in DC considered the matter in March 1925. Basically, we have a similar pattern as to his issue with the Board of Tax Appeals. Ely applied to the Board of Accountancy to be recognized as a “certified accountant” in DC but his application was denied. He then asked to see his file with them and they refused to share it with him. He asked to see the files of other applicants and was refused that as well.

During the appeal hearing, the Board of Accountancy cited confidentiality issues and noted that while they had no issue with his citizenship, moral character or education, they questioned whether the laws in the State of New York regarding the certification of accountants were equivalent to those of the District of Columbia. After considering the arguments, the Court of Appeals affirmed the earlier judgment against Ely. He would not be practicing accountancy or acting as an attorney or agent during tax appeals, at least not in the District of Columbia. Courts 7 (or 8?), Ely 0. It’s hard to keep track since many of these cases went through several different courts.

Perhaps it was these failures to expand his tax accounting business that ultimately convinced Ely to focus his attentions elsewhere. While we have see earlier echoes of his fixation on helping aliens with visa and passport issues, the latter part of the 1920s would see that aspect of his business take off. But before we get to that, we need to take a slight detour to Montreal.

Speeding to Montreal for a Beer

Ely might have been considered a “clever little fellow” by some, but this next episode is comical to say the least. On 25 September, 1925, Ely was due to appear in court to face charges of speeding. Sounds pretty simple. He had apparently been caught driving at 32 miles an hour on Riverside Drive in Manhattan, between 184th and 189th Streets. While 32 miles an hour might seem like a fairly pedestrian pace today, back in 1925, this was quite excessive. The in-town speed limit in many states was 15 mph, while the in-the-country speed limit was 25-30 mph. Many of the cars of the day struggled to reach 45 mph. A comparable infraction today would be doing 60 mph (highway speed) in a 30 mph (city speed) zone. It seemed like a pretty simple case. Driver was caught speeding. Driver then pays the ticket and continues on his merry way. But Ely was not a typical driver.

The Warrant Officer, John McNamara, appeared in court on 24 September, and handed a telegram to the Magistrate, Charles A. Oberwager. The telegram had been sent by Goldsmith, who was happily ensconced in a Montreal bar, sipping a cold beer. The telegram read:

An ill-wind for some one else and a God-send to me compelled me to suddenly depart for this benign country, where prohibition is but a nightmare and where a man can openly quench his thirst with malt beverages of suitable strength. I can, therefore, not keep my appointment with you on my return. Should you have any difficulties show this telegram to Presiding Magistrate Oberwager. Thanks in advance. (The New York Times, 25 September 1925)

The NYT did not record the response of Oberwager but did provide a quick summary of some of Ely’s latest exploits, noting his efforts to stop the Jewish Press from allowing fraudsters to advertise that they were certified public accountants. Apparently, in 1924, Ely also criticized New Jersey justices for their method of handling motor law violators (perhaps he got a ticket there) and had found fault with income tax laws.

About a week later, on 2 October, Ely finally appeared before Magistrate August W. Glatzmayer, who apparently had a sense of humour. According to a NYT article published on 3 October, Ely pleaded guilty to speeding on 12 August and apologized for being 50 days late. He was to have initially appeared before the courts on 13 August (the day after his speeding violation) but failed to appear. Finally, he had sent the telegram implying that he couldn’t appear because of business in Montreal. The Clerk of the Court had sent a telegram in reply urgently requesting he return to answer the charge as his disregard for the summons was a reflection on “the dignity of the court”. Ely did not reply to that telegram either.

And then, on 2 October, he “smilingly walked into court” and stated that he was ready to enter a guilty plea. The magistrate questioned him and Ely stated that he had to attend the “Dry Voting League in Canada”. The judge and Ely then had a conversation that seems to included coded references to alcohol.

Judge – Did you play any of the places up there?

Ely – Once in a while, your Honor, I did knock them off.

Judge – Did you try it out yourself?

Ely – Yes, I did.

Judge – What did you pay for it?

Ely – $3.50 a quart. (The New York Times, 3 October, 1925)

The judge obviously had a sense of humour and, after staring at the ceiling, said “Well, I’ll tell you what I’ll do, I’ll fine you seven quarts at Canadian prices and…” Ely protested “But, your Honor, they search all persons crossing the border… and it is hard to smuggle it in.” The judge said, “Well, you may pay the equivalent in American cash. According to the article, Ely “smilingly paid the fine”, a grand total of $24.50 (worth about $450 today). I’m not sure how this interaction really supported the “dignity of the court”!

The year 1925 was a busy year for Ely with him losing his fights with the Board of Tax Appeals (DC), the Board of Accountancy (DC) and the traffic court. But it also marked the year where he began to embrace the immigration aspects of his business and consequently comes to the attention of immigration authorities.

Trying to Find a Crack in US Immigration Law

As early as 10 August, 1925, case notes of the immigration and naturalization departments (IND) noted that Ely had been running advertisements stating that he could assist aliens in the US by procuring passports and immigration visas for them. Ely had been in their sights for a while, and they wouldn’t lose track of him.

We also get a better sense of why Ely hared off to Montreal in September. It wasn’t just for a “real” beer. The IND files note that, according to the Montreal office, Ely was attempting to legalize the entry of deserting seamen and forwarded a copy of the form he was using to secure the illegal entry of aliens into the USA. Apparently some crew members had deserted from the SS Veendam, a Holland-America line steamer. Whatever tricks he was trying to use, the immigration and naturalization department was getting a rapid education in his methods. On 17 November, 1925, one IND case file had another tidbit from the Montreal office. Apparently Ely had written a “threatening” letter and announced that it was his intention to secure a writ of mandamus from the Supreme Court in order to “compel” the American Consul to issue a passport visa to a woman named Rosa Porter. A writ of mandamus is essentially a court order compelling a government official or entity to perform a duty that is mandated by law. Ely is beginning to sound more like an immigration attorney than an accountant. This trend would only escalate.

On 13 March, 1926, Ely appears in an article in the NYT in a case against Secretary of State Kellogg, Secretary of Labor Davis and Harry E. Hull, the Commissioner General of Immigration. According to the article Ely was acting on behalf of Morris Kaufmann, a wealthy plumbing contractor in Detroit, who was seeking a writ of mandamus to force the above-named officials to issue a visa for Kaufmann’s brother. Ely was arguing the these officials were barring thousands of aliens from visiting America through an arbitrary and unlawful exercise of power. Never mind that the Immigration Act of 1924 had severely restricted the number and type of immigrants admitted to the United States. For Ely, that was beside the point. He was going to press against the legal strictures of the US immigration system until he found a way to get his clients into the USA.

On 20 July, 1926, Ely again appears in the NYT, this time over an issue of duty free limits at border crossings. Apparently, US citizens used to be allowed to bring $100 worth of goods back across the border, duty free, after a three day trip. Apparently, border officials were demanding duties stating that the Treasury Department had ruled that in such cases citizens should not be classed as “residents returning from abroad” and were not entitled to the $100 exemption. The Treasury Department, for its part said that this policy had been in place for years but had not been strictly enforced. A recent ruling by the Customs Court in New York had given sharper teeth to the policy which was now being strictly enforced. Citizens who had been in Canada for less than 3 days were, indeed, being charged duty on their purchases. The fact that Ely had time for all of these legal windmills is impressive. Or concerning. The man seems slightly deranged at times.

In August 1926, Ely appeared before the United States District Court in Vermont of behalf of four individuals who sought to enter the US from Canada to visit family. All four had valid passports for their countries of origin (Finland, England/Russia, Finland, Poland) and stated that they did not wish to “immigrate” to the USA, they just wanted to “visit”. All four had applied to the American Consul in Montreal for a visa to enter the US and all had been denied. The four had tried to enter the US individually at various times but on this occasion, they all appeared together at the same point of entry, St. Albans, VT. Given that they lacked visas, the immigration officer refused them entry. Ely and his fellow attorney wished to argue that the American Consul had no right to withhold the visas and should have provided them to anyone who presented themselves. Ely argued that the American Consul had no right to satisfy himself as to whether or not the travelers were indeed traveling for pleasure/business, or whether they sought to immigrate. He should just issue visas to whomever appeared. Ultimately, the District Court upheld the authority of the American Consul and the four hapless individuals were not permitted entry to the US.

Whether Goldsmith charged a fee to the four individuals or whether he was prodding and testing the integrity of the border process, is unknown. But his efforts would not be stopped by this ruling. A year later, on 1 November, 1927, one of the cases appeared before the Circuit Court of Appeals. Ely and a couple of attorneys argued that the British/Russian individual should not have been denied entry. Why they only chose to appeal the one case is not known. Perhaps this was another testing and prodding of border security and the immigration and justice system. Of course, the appeal failed and the lower court ruling was upheld. Essentially, the court said that if the individual had a problem with a visa not being issued by the American Consul, then the country in which she held citizenship needed to file a diplomatic complaint. Of note here is that one of the attorneys representing the woman was a man named Harold Van Riper. We will hear more about him later as he was woven ever deeper into Ely’s network of immigration fraud.

Earlier in 1927, on 9 March, the Decatur Evening Herald (Illinois) ran a small news article which featured our friend Ely.

Kellogg Named in Suit for $500,000

WASHINGTON, March 9 [1927] – Secretary [of State] Kellogg; American Consul-General, Carlton D. Hurst; Foreign Service Officer Coert DuBois, and American consuls, Arthur C. Frost and Edward Caffery, were sued today for $500,000 by H. Ely Goldsmith of New York.

Goldsmith, self-styled consultant in immigration matters, charges Kellogg and the others formed a conspiracy to keep him from conducting his business by neglecting their duty in issuing passports caused him to lose money.

The Martinez Gazette in California ran a similar article on 10 March, 1927, with a few additional details:

Washington–Suit for $500,000 damages was filed against Secretary Kellogg and other State Department officials today by H. Ely Goldsmith, New York, who charged a conspiracy to refuse to permit certain of his foreign clients to make temporary visits to the United States. Goldsmith says he had retainers of more than $100,000 from nearly 300 applicants for visas.

Our “bright, clever little fellow” had gumption. His suit would be worth about $9,000,000 USD today. Not an insubstantial amount. And it would appear he had about $1,800,000 (in today’s USD) of retainers for 300 clients which would be about $6000 per person in today’s USD. That’s just the retainers. Obviously Ely had a lucrative little business churning away, attempting to turn illegal aliens into legal visitors to the US.

On 25 October, 1927, the NYT ran another article featuring Ely. He was acting on behalf of one Sam Gordon, a citizen of Springfield, Illinois. Sam, born in Lakavitch, Russia, had entered the US on 5 December, 1913, as “Israel Gorendar”. He had Americanized his name and when he sought to get citizenship, the immigration officials could find no record of his arrival. Ely sought to view the ship’s passenger lists but was refused as they were considered the private property of US immigration officials. Ultimately, Ely (and Sam) were successful, for by the 1930 US Census, Sam Gorden is a naturalized US citizen. Courts 22, Ely 1.

In December 1927, Ely’s name surfaces again in another case before the United States District Court, New York. Two individuals who lived in Niagara Falls, Canada, had been commuting daily into Buffalo for the purposes of employment. Neither individual wanted to reside in the USA, they just wanted to work there, and live in Canada. But according to the Immigration Act of 1924, they really needed to have an unexpired consular immigration visa. Without that, they couldn’t enter the USA. Ultimately the District Court upheld the original ruling and the two were deported back to Canada. Another failed attempt for Ely. One of the immigration files notes that Ely used this scheme “to harass” the immigration service.

Dog Licenses & Confiscated Crackers

But lest we think Ely was solely focused on making his fortune with desperate illegal aliens… a 6 January, 1928, article from the NYT is a real eyebrow-raiser. Ely sued the SPCA (yes, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) to allow him to inspect its license records so that he could obtain the list of 200,000 dog owners in NYC.

He wished to send all of the dog owners a letter urging their support of a commercially unsuccessful animal hospital (American Hospital and Home for the Care of Pet Animals). The SPCA charged a license (an early version of a municipal dog license, I presume) and issued a dog tag to registered owners. Ely planned to send out similar metal tags to dog owners that they could attach to the dog collars. If the dog was lost, the tag would encourage the finder to bring the dog to the animal hospital where a reward would be paid. The bigger plan was that the recipient of such a dog tag would make a contribution to the hospital.

The SPCA naturally refused to share its records with Ely (and also with manufacturers of dog biscuits, muzzles and mange cures). They said the metal tags would cause confusion about licenses and might “encourage the theft of the pet animals for the sake of the rewards offered”. Ely argued that the SPCA’s refusal was “unlawful, arbitrary, tyrannical and unfair”. He said that since the society collected dog taxes, its records on such taxes should be open to taxpayers. On 4 February, Supreme Court Justice Levy ruled that the SPCA did NOT need to open its dog owner records for public inspection. Courts 25, Ely 1.

Ely himself also had some trouble when crossing the border at one point, a rather comical incident reported in a 16 February, 1928, Washington Post article. Under the headline “United States Court of Customs Appeals” is a list of case numbers with companies and individuals who had been assessed customs penalties or had items confiscated at the border. Our friend Ely appears here:

No. 3012. H. Ely Goldsmith vs. United States. Personal effects: crackers. Dismissed upon stipulation.

I can only deduce from this that Ely had had “crackers” confiscated at one of his many border crossings. Whether these were: (a) edible crackers; (b) Christmas crackers; (c) other small fireworks; is unknown. I tend to think they were likely the explosive variety, not the edible variety. Although, if he was importing cases of edible crackers, that could possibly have triggered a confiscation.

As 1928 progressed, Ely began to appear in the news with increasing regularity. His fanatical mission to crack the walls of US immigration law seemed to make headway in March. The Expositor ran an article on 8 March which stated that the US Circuit Court had declared that the border restriction rule for commuters was illegal. Ely served notice on the Secretary of Labour that he wanted six aliens to receive immediate admittance to the US for daily commuting to work. The Assistant Secretary of Labor stated that the department would not change the ruling (barring such individuals) until the Supreme Court had ruled on the issue.

The Ice Begins to Crack

On 23, March, Ely was in the NYT again, and this time he wasn’t bringing a case before the courts, it was he who was being dragged before the courts. He had been charged with offering a “faulty writ”. He was fined $150 after he had been found guilty of contempt of court for improperly presenting a writ of habeas corpus. On 3 February, Ely had presented the writ on behalf of an immigrant detained at Ellis Island. In presenting the writ, he had used his own name as well as that of attorney Harry Van Riper (we heard about him earlier). The prosecuting attorney stated that Ely had no right to present the petition because he was not a lawyer and Van Riper, who had represented Ely in the past, had not authorized the use of his name in this case. Charges against Ely for practicing law without a license were now pending. And these were potentially serious charges.

Conclusion

Ely had been in and out of court rooms for almost a decade, generally as the plaintiff. He had dragged the Board of Education through the courts, as well as the Jewish Press, the SPCA, the Board of Tax Appeals, the Board of Accountancy and probably a number of other defendants about whom we know nothing. But as the 1920s were waning, and the Great Depression loomed on the horizon, Ely had finally been cornered. Practicing law without a license was not as easily dismissed as a speeding ticket. And as the 1920s ticked over into the 1930s, Ely will get a different view of the American justice system, from the inside.

H.Ely Goldsmith Blog Series

Part 1 can be accessed here – 3 October, 2024

Part 2 can be accessed here – 10 October, 2024

Part 3 can be accessed here – 17 October, 2024 (link not live until then)

Part 4 can be accessed here – 24 October, 2024 (link not live until then)

Part 5 can be accessed here – 31 October, 2024 (link not live until then)

References

Board of Tax Appeals Case: Goldsmith v. BD. Of Tax Appeals, 270 U.S. 117 (1926). (loc.gov)

Board of Tax Appeals Case: GOLDSMITH, Certified Public Accountant of State of New York, v. UNITED STATES BOARD OF TAX APPEALS

Board of Tax Appeals Case: H. ELY GOLDSMITH v. UNITED STATES BOARD TAX APPEALS | Supreme Court

US District Court – Records and Briefs of the United States Supreme Court – Google Books

Accountant’s Directory Who’s Who – 1920 – Accountants’ directory and who’s who (core.ac.uk)

Ancestry – Image of H. Ely Goldsmith – Ancestry Tree

Ancestry – various genealogical sources

The New York Times – numerous articles

NYC – Vital Records Scanned – https://a860-historicalvitalrecords.nyc.gov/search

NYC – The City Record Online – http://cityrecord.engineering.nyu.edu/

Header Image from FamilySearch